- Home

- Duncan Lay

Risen Queen Page 5

Risen Queen Read online

Page 5

‘No thanks are necessary. You have earned the admiration of this town with your actions at the battle and my respect since I have met you. Anyone else?’

Merren looked around the table and was delighted with the change in them all. The men had a fresh purpose and enthusiasm.

‘Not bad for some peasant scum, eh?’ Gratt nudged Conal, who was flushed with pleasure.

This raised a chuckle, which was broken by Karia.

‘I’ve got a question: who’s going to look after me?’

Merren waved down the chuckles.

‘You will be coming with us to Gerrin. The passes can be taken by force but we may have need of your magic. Besides, the presence of a small girl will help convince them of our goodwill.’

Martil looked up, realising that he would be without Karia again.

‘But, your majesty—’ he began.

‘I’m sorry, Captain, but our need is greater than yours,’ Merren said. ‘Besides, night marches and attacks on garrisons is hardly the place for a small girl.’ Also, if she stays with me, I can use her to keep Barrett away, Merren thought.

Martil wanted to protest more but had to admit Merren had a point. Karia would not only be safer with the Queen, she would also be more useful. And he knew Karia liked Merren. He could not be so selfish as to drag her along.

He nodded. ‘As you command, your majesty.’

Merren smiled. The news about Gerrin and Gello’s use of bards had stung but she now felt curiously energised, more than ready to fight back. She could see the mood around the table was also different although Karia was looking decidedly put out.

‘Gentlemen, you have your tasks. Do not waste time,’ she commanded, and they sprang into action.

3

Archbishop Prent dismissed the servant girl and watched with satisfaction as she gathered her clothes from the floor around his bed and hurriedly dressed. There was no doubt about it—power did have its privileges. He thought about asking her to pour him a fresh goblet of wine before leaving but decided against it. She had worked hard enough that afternoon already. Prent stretched before slowly dressing himself and wandering into his office. It was always a thrill to pull on the golden robes of the archbishop. It was a greater thrill to know he did so while their previous wearer, Archbishop Declan, languished in a penitent’s cell far beneath him.

Still, he had some concerns that day. He was archbishop in name, and had Gello’s backing to be archbishop in deed. But much of the priesthood was fractious. He was owed favours by many senior members of clergy, which was helping keep a lid on any trouble, but there were some, mostly women, who were protesting about some of his decrees. And one bishop, called Gamelon, some hick from the east of the country, was even trying to stir up support against him. Well, it was time to show them once and for all just who was in charge around here.

He had met with King Gello that morning to discuss a new range of sermons, designed to expound on what was already being sung by bards across the country. Gello felt—and Prent agreed with him—that if the priesthood was reinforcing what the bards were saying, then even the doubters would be swayed. ‘We need to be all singing from the same hymn book,’ was how Gello had described it.

Prent just had to make that reality. It should be simple enough—send out the new sermons with orders they were to be preached over and over. Fight against the Queen, stand with Gello, protect the holy land of Norstalos. Simple enough words, for a bunch of simple peasants. And anyone who refused to preach these sermons would be arrested, securing the priesthood and pleasing Gello in the one action.

He was congratulating himself on how easy it was to be the archbishop when a young servant girl—a different one this time—disturbed him.

‘Archbishop, I have two messages here, people requesting a meeting with you,’ she said nervously.

‘Come in, my dear. Don’t be frightened,’ Prent smiled wolfishly at her. Archbishop Declan had used recent graduates from the seminary as his secretaries but why, Prent felt, should he be surrounded by those pious fools when there were so many good-looking young women around? King Gello was right: to the strong went the rewards. And Prent knew he deserved every possible reward.

‘The first one is from the Berellian ambassador, requesting an audience, the second from a retired priest…’ The girl trailed off as Prent waved his hand in dismissal.

‘I’ll see the Berellian but whoever the old fool of a priest is, fob him off. I don’t want to talk to him,’ he snapped.

‘Yes, but he wants to talk to you,’ a man’s voice said, and Prent spun to see an elderly priest walk through the back door to his office.

‘Who are you and what are you doing here?’ Prent blustered. He made a mental note to post guards on that door as well—he thought most people did not know about that way in.

‘My name is Father Nott—and I am here to warn you about your immortal soul,’ the man said pleasantly. His face was calm as he strolled slowly towards Prent. ‘I have been granted a vision by Aroaril and need to talk to you.’

Prent wasted no time; the old man was obviously addled. He rang a bell on his desk.

The sound seemed to animate Nott. ‘I come here to help you and you call for guards? Prent, you are even more foolish than you look! While you spend your time abusing servant girls and plundering the church’s coffers, there are greater forces at work! The time is coming when you will be forced to make a choice between your life and your soul. Do not make the wrong choice!’

Prent was not really listening to the old man’s babble, just looking for the guards. He was relieved to see them burst through the doors, although when they saw the cause of the alarm, they both relaxed, giving Nott a little more time.

‘Remember one thing from this, Prent, just one thing. There are worse things than death,’ Nott said urgently.

Prent walked over to him, feeling much more confident now his guards were about to haul the old buffoon away.

‘Worse things than death? Such as being lectured by a senile fool who can’t control his own bladder any more?’ Prent sneered. ‘Take this idiot away and don’t let him in again. Aroaril will be coming to claim him any day now—although I don’t know why he would want such a useless lump of whiskers.’

Nott smiled and walked calmly past the guards, back towards the main entrance.

‘Next time I come here, it will not be to talk,’ he promised.

The squad of criminals was seated in a circle, eating hungrily from a cauldron of stew. Kettering had to admit the food was far better than the slop served to a condemned man. There had been other changes since being drafted into the army. The unrelenting physical work had put muscle on his shoulders and arms and what he had gone through had added new, harder lines around his eyes and mouth. Without access to his expensive hair creams, he had been forced to tie his long hair back with a leather thong. He doubted even his most loyal customers would recognise him now—he barely recognised himself.

‘Whaddaya reckon about that bard then, Killer?’ Leigh asked through a mouthful of food. ‘Wasn’t that something? To think we’re going to be asked to go north and fight against the Butchers of Bellic! We’re the filth you wipe off your boot but our country needs us! We’ll be heroes!’

‘Dead heroes.’ A bearded man who had introduced himself as Hawke had attached himself to the group. Unlike traditional army units, the criminal regiment seemed to be fluid in its composition. As long as nobody ran and no company was dramatically bigger than the next, the sergeants did not seem to worry about who was in each section.

‘We won’t die! Not when we’ve got blokes like Killer Kettering leading us,’ Leigh declared.

Hawke snorted. ‘The other side has Captain Martil, the Butcher of Bellic. You heard the bard! All his men are killers! They probably eat human flesh! I heard that Martil is nine feet tall and has sharpened teeth, like a dog!’

The other men listened in awe, the stew forgotten.

‘That is the biggest pack

of lies I’ve heard since my murder trial,’ Kettering growled.

‘What?’ Hawke bristled.

‘I know this Martil. He stayed at the inn I worked at. I’ve talked to him. He was travelling with a small girl, looking after her. The man I met was not the man that bard sang about.’

The other men just stared at him.

‘So you reckon the bard was lying?’ Hawke mocked.

‘Of course he was, you fool! I’ve worked at inns all my life! Every inn hires Rallorans for protection, because they are the best! How many inns have you gone to when the security on the door was eating babies or starting fights?’

‘Maybe they didn’t start them, but they sure finished a few,’ a tall, hulking man with a broken nose offered.

The other men chuckled at that. They had all seen the inside of a few inns—and been on the wrong end of Ralloran security. Hawke, without any support, looked ready to challenge Kettering again but subsided after a warning look from Leigh.

‘Those Rallorans aren’t baby-eating barbarians and Captain Martil isn’t a monster. The monsters are the men who are against him. They were the ones who set me up, sent me here,’ Kettering snarled.

The other men, knowing Kettering’s reputation, eased slowly away from him.

‘But why would they lie to us, Killer?’ Leigh asked nervously.

Kettering thought for a moment. ‘We’re not being given a second chance. After a few more performances like that, they think we’ll just charge right in, kill a few Rallorans before we are all cut to pieces—that way they get rid of us and the Rallorans.’

The other men thought about that—not an easy task for some of them—and none of them liked the prospect of charging battle-hardened warriors, baby-eaters or not.

‘So what are we going to do?’ Hawke asked.

Kettering sighed and stirred his stew listlessly. ‘I don’t know—yet.’

‘How did it go?’

Nott slipped back into his room and closed the door carefully before answering.

‘Anyone around?’ he asked softly.

His female companion shook her head. ‘Not a one.’

Nott sighed with relief. Sister Milly had been a great help to him over the last few days. A former secretary to Archbishop Declan, she was triply despised by the new regime, being also both rich in Aroaril’s favour and a woman.

‘It went as expected. Our lecherous archbishop is more concerned about what is in his purse and what is in his pants rather than what is in his heart. I gave him the warning but I fear it will come to naught. At least I survived the meeting.’

‘You should not have gone, Father! I should have gone in your place!’ Milly burst out.

Nott smiled warmly at her. She reminded him of Mara, his adopted daughter. If she had lived, she would have been a woman like this, he thought. ‘No. He thinks I am an old fool who is going senile. You would not be so lucky. How was your expedition?’

Milly sighed. ‘It is as we feared. Orders have gone out to remove any priest or priestess who refuses to deliver Prent’s sermons. He has had an army of servants clearing out the old penitents’ cells in the cellars, so he can fill them with priestesses as well as priests who rail against him, like your old bishop, Gamelon.’

Nott sat down.

‘Are you all right, Father?’ Milly asked. ‘Would you like some tea?’

‘As I always say, the day I can’t make my own tea is the day I meet my maker. Still, He has told me I have a few more tasks to complete before I finally rest, so boil the kettle and warm the pot.’

‘What did He reveal to you?’

‘Too much—and not enough. He is not finished with me after all—what I thought was my final task was, in fact, just the beginning of them. He asks a great deal and promises nothing but hard work and the prospect of no reward. It is ironic. I was sure my work here was done and felt disappointed I could not do more. Now I learn I have a greater part to play and I wish my role was ended. Already I have had to lose my daughter, tell my granddaughter that I cannot look after her…My trials have been severe. My years of service are being rewarded with bitterness and pain. And I worry what else I must do before the end. Is the future being hidden from me because it will affect what I have to do? Or because I will baulk at what He requires of me? I do not know.’

Nott paused. ‘I do not mean to sound as if I am complaining. I must believe that all I have lost, all I have given up, has been for a greater good. Even though I have not received a sign of hope. All I have seen is that we must be careful but we must start gathering others to help. The time of crisis is upon us.’

He sighed again and Milly felt she would like to embrace the old priest. But she hesitated, and he pushed himself to his feet.

‘Now, excuse me, for there is another time of crisis upon me—the time of passing water.’ And he offered her an outrageous wink.

Milly stopped preparing the tea and looked over at the old priest.

‘How do you do it, Father?’

He shrugged. ‘I just have to have faith.’

Sergeant Hutter accepted his plate of food without much enthusiasm. Boiled beef and boiled vegetables—and not much of either. Only water to wash it down. The other men at least got some gravy.

‘And that’s all you’ll eat until you can see your belt again, fatguts,’ his trainer told him.

Hutter did not have the energy to argue and made his way slowly to one of the tables. Men made room for him and he nodded gratefully.

‘Good show this afternoon, Sarge. I know you love the sagas.’ His young constable from Chell, the gangly youth Turen, seemed to enjoy the training but could still annoy Hutter.

‘Yes, I did like the sagas but that one made no sense,’ Hutter sniffed, trying not to think about stealing Turen’s gravy.

‘What do you mean, Sarge? Those Rallorans are ripping the north of the country apart, we need to learn how to fight so we can go and stop them. Easy!’

‘Constable, how many times have I asked you to use your brain?’ Hutter snapped. ‘We met Captain Martil back in Chell. That was while the Queen was still on the throne. Why would she hire thousands of Rallorans to put her back on the throne if she wasn’t even off it yet? And he spent the night with Father Nott, then left the next day with Nott’s granddaughter, the one that Edil wanted back. You knew Father Nott. Would he have let that girl go off with a murdering barbarian?’

‘No, Sarge,’ Turen mumbled.

‘Something stinks—and not just my sweaty tunic. That Martil was a dangerous man but if he was here to slaughter every Norstaline in sight, like the bard said, why didn’t he start in Chell?’

‘Don’t know, Sarge.’

Hutter grunted. ‘Me either.’

‘So what do we do, Sarge?’

‘Do? We do what we’re told, lad. For now. But I’m damned if I’m going to sweat so bloody hard for some lying bastard to send me to my death.’

‘But why do you have to go? It’s not fair!’ Karia folded her arms, stamped her foot and pouted her lip at Martil.

He was tempted to agree with her but he didn’t think Merren would appreciate him throwing a tantrum. Still, he felt keenly the unfairness of having to explain to Karia something he disagreed with. He also felt guilty about leaving her. He had finally been able to articulate his feelings about Karia but what good was that if he was not around? She needed stability in her life, not more change. How he was going to give her stability in the middle of a war was an impossible question to answer.

‘Because I have to. Adults have to do things they don’t want to, sometimes, just like children have to do things they don’t want to.’

‘Like going to bed when I’m not tired?’

‘Something like that,’ Martil agreed. ‘Believe me, I wish I was staying with you.’

‘I want to stay with you! You’re the only one who really cares for me! The others all want me to be quiet or go away!’ Karia declared.

‘Well, are we going to argue or

are we going to play while I have time?’ He was still worried about those dreams of Bellic but, around Karia, the fears seemed to vanish.

‘Play! Catch first, then dolls, then you can read me some stories…’

‘Come on then.’ Martil smiled as he followed her out of the room. It would be a brief respite. He had Nerrin and Kesbury gathering supplies for the march south. Despite Nerrin’s confident words, taking all three passes without significant losses would be difficult. But at least the men seemed pleased to have a purpose—in the short time they had been back, four men were on a charge for sneaking into town and getting drunk, while several fights had broken out. Discipline had been restored but this was not the same proud, confident fighting force he had led out of Sendric just days ago. They needed a victory, and the chance to fight back at those they saw as responsible for spreading the stories about Bellic.

King Gello looked at the map with relish. He had expanded the Royal Council to include his war captains, while the Berellian, Ezok, was now a regular spectator.

‘So Lieutenant Bayes in Gerrin reports the Ralloran scum marched away, and Berry has not seen hide nor hair of the creatures. Meanwhile, the performances to our new regiments have them in the right frame of mind to go north and attack. I can see my foolish slut of a cousin now—scurrying here and there like a frightened mouse, not knowing where to turn for help or where to go. We have her surrounded and outwitted and, in a few months, we can go north and crush her like the insignificant ant she is.’

All of the captains immediately applauded his statement and, seeing this, the nobles did too.

‘Once our north is secure, we can turn our attention to outside our borders—and the real rewards will flow then, gentlemen! All the riches of the world are there for the taking—to the strong go the spoils! Land, gold, women—we will take them all!’

This time the nobles were among the first to cheer. But a grinning Gello noticed that Ezok did not seem to be joining in the general celebration.

The Radiant Child

The Radiant Child The Poisoned Quarrel: The Arbalester Trilogy 3 (Complete Edition)

The Poisoned Quarrel: The Arbalester Trilogy 3 (Complete Edition) Radiant Child

Radiant Child The Wounded Guardian

The Wounded Guardian Bridge of Swords

Bridge of Swords The Bloody Quarrel (The Complete Edition)

The Bloody Quarrel (The Complete Edition) Valley of Shields

Valley of Shields Risen Queen

Risen Queen The Risen Queen

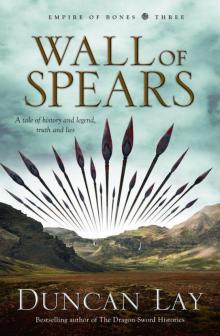

The Risen Queen Wall of Spears

Wall of Spears